A Foreign Affair

Alien Patriots

by Daniel Shippey & Michael Burns

When we think of the patriots who sacrificed for American Liberty in the Revolution we recall images of the Minutemen at Lexington and Concord, the Continental Army at Valley Forge or Francis Marion’s ragged militia. Our history teachers, in the rush to get across simple concepts and quick answers for Friday’s test, largely left out the names of foreigners who made major contributions to the cause of Liberty. Names like Thaddeus Kościuszko, Casimir Pulaski, Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben and the most famous of our foreign volunteers, Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette. These are only a tiny sample of names belonging to those who came from foreign places to offer their service. There were thousands when you add in Army & Navy volunteers, foreign naval support, or even financial support that came from places like Spain, France, Holland and Native American allies. Throughout the war these foreign Volunteers served, led, fought, were killed, were injured, were made prisoners and finally helped bring victory to the United States. What brought them to America? What motivated them to fight for another country? What were their lasting contributions? Any one of the four names above is worthy of their own book, but for the moment let’s just take the first name on the list and look a little further.

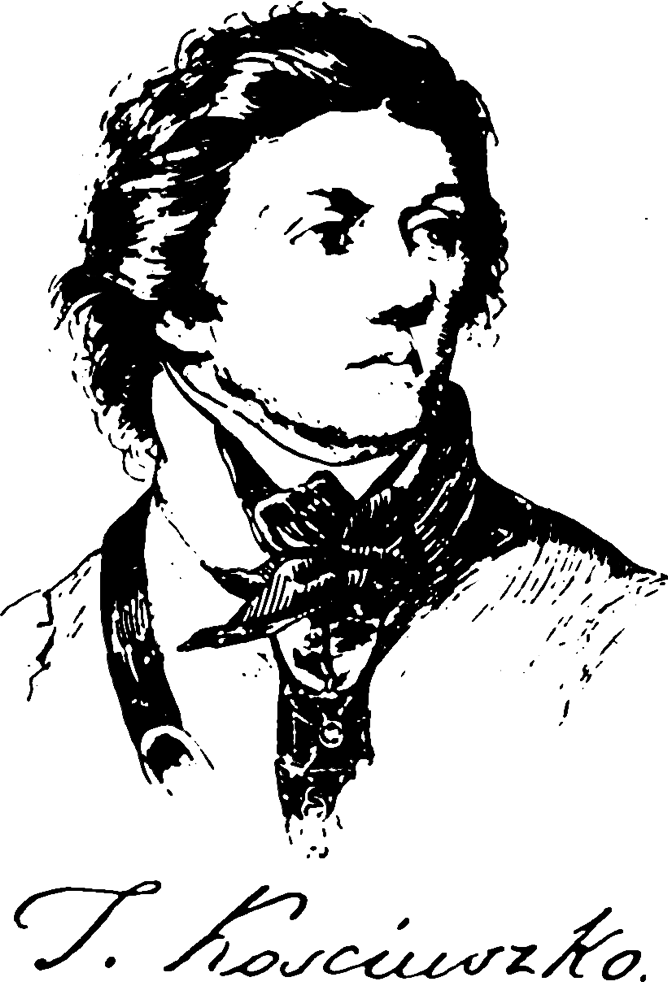

It has been said that when Thaddeus Kościuszko (KOS-CHOOS-KO) first read the Declaration of Independence he wept, for in it he had found a document that encompassed all that he held true.

Kościuszko was born in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (today Belarus) in the year 1746. Being the youngest child of a local noble often meant a future in the army, for the oldest son would have the title, and the next might become an important bishop in the church, but the options were limited for the third son. Thaddeus seemed to embrace the idea of military life, and determined to gain education as an officer in Warsaw at the Knights' School Cadet Corps. There, his skill at geometry won him a place in an engineering course for outstanding students. He flourished at the school with a surprisingly wide range of studies. Kościuszko graduated and stayed for some time as an instructor at the school, having achieved the level then referred to as “master” and the military rank of Captain. After a time, he left the Knight’s School to pursue further education in France. As a foreigner in Paris he was not allowed to join the military academy, so he studied painting. Though he became a skilled painter, Thaddeus found himself unwilling to focus solely on fine art. He returned to his study of the military arts on his own. He attended lectures everywhere, including the academy as a visitor. These educational experiences in Poland and France left him with skills in languages, law, geography, arithmetic, geometry, engineering, philosophy, economics, military strategy and the fine arts. The breadth of knowledge he amassed is fairly astounding. His time in Paris also introduced him to the philosophy of the Enlightenment. This was a subject that he may not have intentionally set out to study, but that would direct and dominate the rest of his life.

In 1772 Russia, Prussia and Austria annexed large portions of the Polish-Lithuanian territory and Thaddeus returned home to fight. It seems that the Polish-Lithuanian government lacked Kościuszko’s fortitude and quickly began to negotiate away its own power. Soon, as part of its negotiations, the government reduced its army’s size and there was no place for Kościuszko. Educated and trained with no options for his employment of choice, he took a job as a tutor for the noble family of Sosnowski, where fell in love with one of his students, Ludwika.

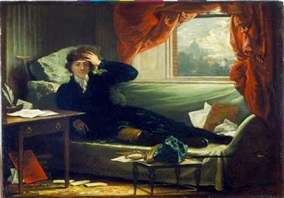

The series of disappointments continued for Kościuszko. He sought a position in the court at Dresden and again found no place for his intellect or his sword. Finally by 1775 he returned to Paris. Here in France he heard about the early struggles between America and the British crown. All of his enlightenment ideals, as well as his personal struggles against rank and injustice, seemed to be embodied in the American cause. Traveling and equipping himself at his own expense, he came to the colonies to join what he saw as a fight for the principals of liberty. Soon after he had arrived in Philadelphia in August of 1776 he presented himself as a volunteer to the Continental Congress with letters of recommendation from Charles Lee and Prince Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski. The story is told that when Kosciuszko was sent to Washington, their first meeting went as follows.

"What do you seek here?" inquired the General.

"I come to fight as a volunteer for American independence," answered Kosciuszko.

"What can you do?"

"Try me," was his quick reply.

He became a member of Washington's “military family”, October 18, 1776, as the ranking colonel in charge of engineers.

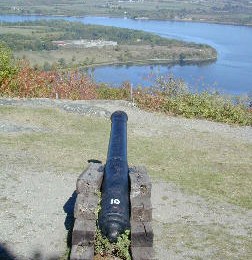

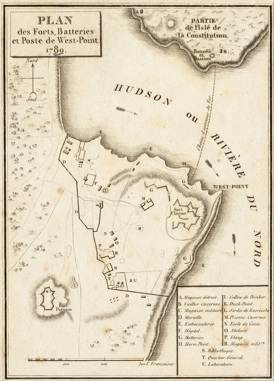

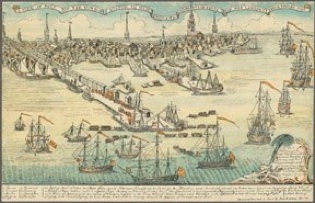

Kościuszko’s first assignment as head engineer was to fortify Philadelphia from attack by the British Navy. He produced a series of excellent forts, well designed and placed downstream of the city. By 1777 he had overseen the construction of forts as far North as Canada. Dispatched to the captured Fort Ticonderoga, he began work on a series of repairs and plans to assure that it could not be retaken by the British. He surveyed a glaring weakness in the terrain and strongly advised the building of a battery on Sugar Loaf Mountain, which commanded the fort. The garrison Commander, Arthur St. Clair, decided against following Kościuszko’s advice.