Ails To The Chief

by D.H.T. Shippey & Michael Burns

“Doc Mark, the British Army surgeon otherwise known as historical interpreter and medical historian Mark Rutledge, once told me a rule of thirds for 18th century medicine. “About one third of the medicine would help you get better, about one third would do absolutely nothing, and the last third would actually make you worse.” Looking at a Revolutionary era doctor’s tools and medicines fills one with questions, amazement, and often nausea. I have stood watching Doc Mark give his lecture to a museum crowd while an audience member fainted just from the description of how a tool was used.

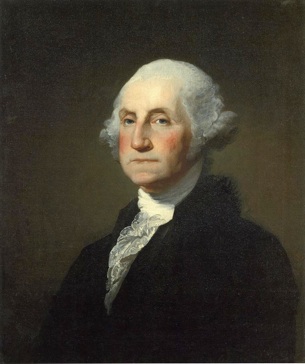

When people ask me if I wish I could live in the 18th century I always answer with a firm, “No, I’d visit but I wouldn’t live there.” That is because, after listening to Doc Mark and others likewise knowledgable in the medical arts of the time, I sincerely doubt I could have survived. Don’t misunderstand me--I enjoy the incredible blessing of good health. I just look at what the people who did live and survive in the era endured and I get the sneaky suspicion they were a whole lot tougher than this 21st century man. Perhaps one of the greatest examples of what I mean can be found in the person of George Washington. Tall for his day, very strong, athletic and tough, the man was known for cracking walnuts between his thumb and forefinger. Surely a model of vitality, strength and health such as he never got sick! Oh yes he did, a lot, but he always survived...until he didn’t. But we will get to the end later.

Washington’s first major illness is believed to have been diphtheria, then called “throat distemper,” when he was around 15 years old. This is a bacterial infection that is spread through respiratory droplets (that would be coughing and sneezing to you and me). There are only about five cases of it a year in the United States today. Symptoms include a bluish coloration of the skin, bloody watery drainage of the nose, breathing problems, fever, chills, etc. Today we have immunizations and treatments, but in the 18th century they had no cure for one of the three deadliest diseases known. While doctors did not have a cure, they did have a “treatment” which included an herbal remedy of rhubarb and turpentine along with raising six blisters on the patient. If that did not prevent the patient’s throat from swelling, he would be bled and treated with Oil of Cedar. Now bleeding always sounds insane to our modern minds, but the 18th century doctors did see some success with it. It would clear out some “tired” blood and the body would replenish the infection fighting white blood cells. The doctors of the period did not know about white blood cells--or germs for that matter--they just knew bleeding seemed to drain off the bad blood. Washington seems to have survived this illness relatively unscathed, but he was never a big fan of medicines afterward.

At 17, Washington contracted Malaria (Ague) the treatment for which was Jesuit powder made from cinchona bark. The bark contained quinine, which remained the best treatment until the 1940’s. Synthetically reproduced, quinine is still sometimes used to treat malaria today, but it is not guaranteed to completely eliminate the parasitic disease from the body. People often had recurrences, with the longest incubation on record being 30 years. Washington would have repeated attacks throughout his life. The symptoms of malaria include high fevers, shaking chills, flu-like symptoms, anemia, and sometimes coma and death.

In 1751, Washington accompanied his older half-brother Lawrence on a trip to Barbados. Lawrence had been suffering from tuberculosis and hoped that the warm, wet climate would improve his health. Soon after arriving, 19-year-old George contracted smallpox. The worst of the big three deadly diseases known, smallpox was a cause of panic in the 18th century world. Backache, delirium, fatigue, diarrhea, bleeding, high fever and of course the blisters for which it was named made up its symptoms. Washington survived, but was scarred with pock marks for the rest of his life. Smallpox would later become an epidemic during the Revolutionary War, but because of his early exposure Washington was now immune to the illness.

We are still only at age 19 when, because of his weakened state from smallpox, it appears that Washington also contracted tuberculosis. His brother Lawrence would die from the disease, but George recovered after several months.

Two years later, Washington was healthy and active with a commission in the Virginia Militia. He joined the staff of General Edward Braddock in an expedition against the French Fort Duquesne (now Pittsburgh) when he was stricken by disease again, this time by what he called the “bloody flux.” Washington wrote in his journal in his diary: "Immediately upon leaving camp at George's Creek on the 14th, I was seized with violent fevers and pains in the head which continued without intermission until the 23rd following when I was relieved by General Braddock's absolutely ordering the physicians to give me Dr. James' powders, one of the most excellent medicines in he world for it gave me immediate ease and removed my fevers and other complaints in four days time. . . ." Washington caught up to Braddock and at the battle of the Monongahela, so ill he could barely mount his horse, he is credited with saving much of the badly defeated British force. After the battle, he returned to Mount Vernon and wrote his surviving brothers that he had been ill for "five weeks duration."