by Dan Shippey &

Michael Burns

“But ALL FOR LOVE is my motto.”

Alexander Hamilton

Most Americans today think of the Revolutionary War era as stuffy and passionless. Our Founding Fathers and Mothers would have been surprised to hear that. True enough, George and Martha didn’t have Barry White albums, speed dating or honeymoons in Vegas--but they did have romantic ballads, balls and handfasting.

Many of our founders left records of their courting in their letters and family stories. John and Abigail Adams wrote passionate letters to each other. They adopted pen names like Diana (the chaste and beautiful Roman goddess of the moon) and Lysander (the Spartan war hero). Often John addressed his letters to Abigail as Dear Adorable. Thomas Jefferson is said to have heard the widow Martha Wales Skelton singing in her Williamsburg home. Knowing that this meant she had completed her mourning period for her late husband, he jumped off his horse and grabbed his kit (small violin) from his saddlebag. Presenting himself at the door, he inquired if he might accompany her in a duet. We will never know about the intimate nature of George and Martha Washington’s love because she burned all of their correspondence to keep it private. What we do know, from the few writing examples that survived, is that he doted on her and she fondly called him her “old man.” Washington proposed marriage just three weeks after he met Martha. During the war, Martha took every chance she got to make the dangerous journey to stay with the General in camp, and when she was gone he pined to be home. Every night of their 40 year marriage that they were not separated by business or war they slept in the same bed. When he died, Martha closed the room and never slept there again.

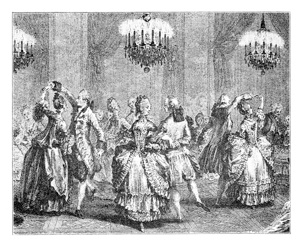

Opportunities to meet members of the opposite sex were special occasions in the 18th century. Going to church, balls, parties, public entertainments or a friend’s home to visit were some prime places for young men and women to meet. Normal rules forbade speaking to a member of the opposite sex in the street until you had been introduced. Once you had met someone of interest you did not “ask them out on a date,” but asked if you might call on them (at home) during the day. This guaranteed that your visit would be safely chaperoned. Often you might spend time in the family parlor while you visited, possibly with other family members around. Walks were allowed so that a young couple might stroll and have private conversation, but a man was expected to act honorably. Oddly enough, women (being the daughters of sinful Eve) were thought of as being more likely to have lustful tendencies; a man was expected to show self control.