National Treasure

Book of Merit

by

D.H.T.Shippey & Michael Burns

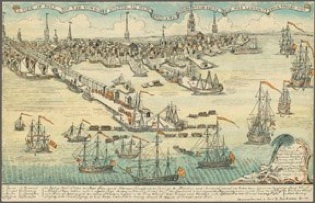

There are many National Treasures from the Revolutionary Era that have been lost to time. Martha Washington burned the personal correspondence between herself and George after his death. The American Turtle, first submarine ever to attempt an attack on an enemy warship, has itself vanished beneath the waves of time. One of these lost National treasures is the Book of Merit. This book held the names, regiments and actions of those soldiers who had earned the Badge of Military Merit, an award that was itself revolutionary.

In the 18th century, countries gave ribbons, medals and awards to officers whose victories or valorous actions were recognized by their superiors. This was an era when only gentlemen who purchased their commissions could become officers. Private soldiers were given little thought and could achieve little distinction. In America there were very few people of genteel birth—certainly not enough to fill the military’s desperate need for officers. While many of the early New England officers were chosen by a vote of their men, this system was shown to be a dismal failure from the outset. Any officer who gave a difficult order might find himself voted out of power. Merit must be the new criteria for greatness in the American republic. General George Washington recognized this and encouraged it, raising some from obscurity to the rank of Generals in the course of the war. But in August of 1782 Washington saw the need to recognize regular soldiers who distinguished themselves in service or combat. To this end he gave orders establishing two decorations. The first of these awards was the Badge of Distinction, a white strip of cloth sewn above the cuff of a soldier’s coat denoting three years of service. This is a tradition that is carried on today in the form of hash marks. The second of these awards was The Military Badge Of Merit. This award was created to recognize both regular soldiers and officers for “Singularly meritorious service.” The order read as follows:

“The General ever desirous to cherish virtuous ambition in his soldiers, as well as to foster and encourage every species of Military merit, directs that whenever any singularly meritorious action is performed, the author of it shall be permitted to wear on his facings over the left breast, the figure of a heart in purple cloth, or silk, edged with narrow lace or binding. Not only instances of unusual gallantry, but also of extraordinary fidelity and essential service in any way shall meet with a due reward. Before this favour can be conferred on any man, the particular fact, or facts, on which it is to be grounded must be set forth to the Commander in chief accompanied with certificates from the Commanding officers of the regiment and brigade to which the Candadate [sic] for reward belonged, or other incontestable proofs, and upon granting it, the name and regiment of the person with the action so certified are to be enrolled in the book of merit which will be kept at the orderly office. Men who have merited this last distinction to be suffered to pass all guards and sentinals [sic] which officers are permitted to do. The road to glory in a patriot army and a free country is thus open to all. This order is also to have retrospect to the earliest stages of the war, and to be considered as a permanent one.”

The words “The road to glory in a patriot army and a free country is thus open to all.” demonstrate that Washington was very aware that he was changing the rules. Men would be valued and rewarded for what they did, not by the circumstances of their birth.

The Book of Merit was meant to chronicle the deeds of the new nation’s heroes. It disappeared sometime after the war came to an end. What happened to it? Is it mislabeled in a library or lost among government documents? Was it destroyed in some tragic fire or neglected and disintegrated with the passing of time? Was it put somewhere for safe keeping and today waits to be discovered in some descendant’s attic? Nobody knows. Right now The Book of Merit remains a lost national treasure that historians can only speculate on based on the information we still possess. We know the names of the first three recipients of the badge of Merit, but researchers have diverging hypotheses as to whether these were the only recipients or just the first. There is no complete listing of their actions warranting such distinctions. Historians can theorize from the regiments and brigades and the date of the nomination what the deeds of the nominees were. Still, those details we want can only be guessed at.