Hey Brother, Can You Spare A Peso?

The 1st in a series of articles about Spain’s forgotten contributions to American independence.

By Eric B. Ramey

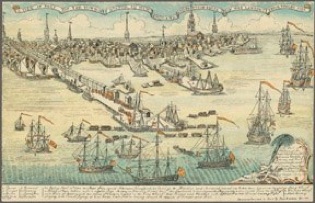

When the Revolutionary War erupted in 1775, Spain saw a golden opportunity For revenge. Walter Raleigh, Francis Drake and Henry Morgan are but a few 16th and 17th century names synonymous with daring British raids of the Spanish Main.

St. Eustatius, a Dutch possession at the far eastern end of the Caribbean, became, in effect, the marshaling point for foreign aid and supplies sent to the new United States. The island was a veritable “shopping destination” and provided the latest in goods to those who could afford it. At any given time, one could find an assortment of expensive imported silks, rich with embroidery, painted and printed cotton calicos, gloves, fine stockings, clothing and goods sure to satisfy even the richest tastes. In 1779 alone, St. Eustatius received and shipped over twenty five million pounds of sugar to destinations around the globe. So much wealth passed across its shores that the island was known as “The Golden Rock”. In addition to goods and raw materials, the traders and agents of St. Eustatius privately obtained a variety of military supplies from Spain, Holland, France, Portugal, even England, and promptly provided or sold them to the United States.

If St. Eustatius was the marshaling point, then New Orleans was the distribution conduit. Originally a French colony, New Orleans was given to Spain by France after the French and Indian War, as reparation for the loss of Florida. Sitting at the terminus of the Mississippi River, the city was perfectly situated to send much needed supplies upstream to the Continentals. Jose de Galvez, Spain’s Minister to the Indies was instructed by his king to lend as much support as possible to the struggling Americans. In response, tremendous amounts of supplies were shipped up the Mississippi by the Spanish. Muskets, cartridge boxes, uniforms, shirts, lead, gunpowder, medicine and food spread out from the Crescent City, making their way to the Continentals by barge and by ship. Between 1776 and 1779, Spain gave the Americans lines of credit and loans totaling roughly eleven million, over three hundred thousand pounds of gunpowder, over two hundred cannons, and thousand upon thousands of musket balls, muskets, bayonets, tents, grenades, bayonets, uniforms, shirts and shoes. After three years of covert support, Spain declared War on Great Britain in June of 1779, and overtly turned its forces in the Caribbean to supporting America’s Revolution.