Coffee, Tea and Conspiracy

by

D.H.T.Shippey & Michael Burns

He was one of the most infamous Tories in the War for Independence, a royally commissioned Printer to the King of England, and a relentless critic of the patriots. He was also one of George Washington’s spies.

His name was James Rivington, born into book selling and printing as a family business in London. At the age of 36 he fled from large gambling debts in England and relocated to Philadelphia. In 1773 (at the age of 49) he moved to New York, where he opened another print shop. An 18th century colonial newspaper was not, on its own, profitable enough to keep a printer fed. Printers had to diversify their products into books, pamphlets, legal forms, art prints, broadsides and the most lucrative work, government (Royal) documents. Still, Rivington’s weekly newspaper, The New York Gazetteer quickly became popular and well known for impartiality in its political reporting. Rivington was known for being a very educated, intelligent and cultured man.

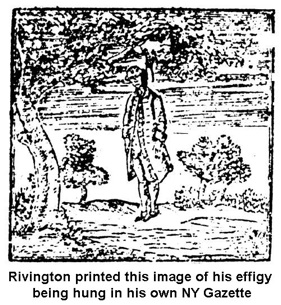

The storm of the coming revolution made it difficult for people in New York to remain neutral. Sides were being chosen, and Rivington’s claim to being an “ever open and uninfluenced press” was an early casualty of the war. He became a supporter of the British government’s restrictive acts and a harsh critic of the patriots. His regular journalistic attacks quickly landed him on the bad side of the New York Son’s of Liberty. It wasn’t long before Rivington was hung in effigy and at his fictional execution a mocking confession/speech was read aloud. Rivington, who knew a good news story and how to spin it, reprinted the speech in his paper.

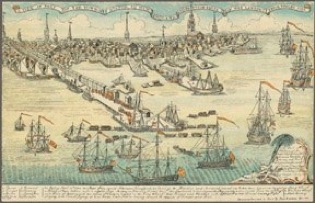

But when news of the shots fired at Lexington and Concord reached New York, the violence went from symbolic to real. Rivington’s house and press were mobbed, and he fled to a British man-of-war in the harbor. With his press destroyed and the lead type melted for bullets James Rivington and his family sailed away for England.

By 1777 the Howe brothers, with the British army and navy, had pushed George Washington and the Continentals out of New York. Rivington returned to the city now holding a Royal commission as “Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty” and started up his new newspaper, Rivington’s New York Royal Gazette. Close by his press Rivington opened a brilliant second business, an upscale coffee house. In the coffee house, men would gather to relax with the newspapers, books and pamphlets Rivington printed and enter into discussions about current events. It was well known that your bill at Rivington’s Coffee House would be dismissed if you brought him interesting news.

If the articles Rivington printed had been unpopular with patriots before, now they made patriot blood boil. Among the stories that appeared were: Benjamin Franklin had been wounded by an assassin and was soon to die; Congress was preparing to rescind the Declaration of Independence; The Russian Czar was sending more than 30,000 soldiers to crush the rebels; Washington (like Cromwell) had been declared Lord Protector; Washington fathered illegitimate children; or (the ever-popular) Washington had died. Governor William Livingston (who suffered great ridicule in the paper) wrote, "If Rivington is taken, I must have one of his ears, Governor Clinton is entitled to the other, and General Washington, if he pleases, may take his head." Rivington’s paper was reviled as the “Lying Gazette” by displaced New York patriots, and even Loyalists felt it was full of exaggeration and disregard for truth. It only makes it that much more shocking to find that this notorious Tory was using his newspaper reporting and coffeehouse to spy for the Patriots.

Nobody knows when Rivington began spying for George Washington, but we do know that he was part of the Culper Spy Ring operating in and around New York. We know for sure that he had begun his double life by 1778 because of documents in the records of Congress that allude to him. It is clear that while he printed and published articles deriding the Patriots and praising the glory of British Arms, he was simultaneously gathering intelligence and passing it through couriers to Washington’s spy chief Benjamin Tallmadge. The system most often employed involved Rivington writing his intelligence reports on very thin paper and then enclosing them in the binding of a book. The book would be sold to one of Washington’s spies and then taken to the patriots’ camp. The constant stream of coffee house clients in red coats guaranteed regular high quality reports.