The Cowboy Way

by D.H.T. Shippey & Michael Burns

There was a time in America where the word “Cowboy” was synonymous with “outlaw.” Specifically, it was the name given to British Loyalist outlaws who raided the farms and homes in New York’s wild west. It can be difficult to imagine New York being frontier territory today. The farms and open spaces have become cities and suburbs, but in many cases the names have stayed the same, allowing us to map out some of the activity of the cowboys and follow the trails of these men. Dangerous men who fought a bitter partisan war within the larger war of the Revolution.

Cow-Boys as they were called at the time were avowed Tories. The origin of the name is said to have possibly come from thieves that would hide just off the road and ring a cow bell. When a farmer would hear what they assumed was a lost cow, they would leave the road in search of it, giving the “Cow-Boys” an opportunity to rob them. But it seems more likely, that the name came from their lucrative business of selling pilfered cattle to the British army. The distinction of “Tories” did not mean that they would only attack and rob Patriots; in fact Cow-Boys would attack and plunder anyone they found a profitable target. Their victims were farmers, merchants, travelers, inn keepers, and even soldiers if caught alone or in small numbers.

Lying between the two armies, the area of Westchester County, NY became known as the neutral zone. Trying to hold on to your property in the neutral zone was a full time job, with many families choosing to flee and lose everything but their lives and what they could carry. In 1775 Westchester was the richest and most populous county in the Colony of New York. By 1780 it was described by Continental Army Surgeon James Thatcher as a country that, “Now has the marks of a country in ruins.” Armies of the 18th century tended to strip the land they passed through of food and supplies, but the Cow-Boys were not moving between places. They were entrenched gangs that knew the lands they were pillaging.

There were other forces operating in the Westchester area as well. Skinners were the Patriot version of Cow-Boys, with the same sort of variable loyalties when it came to profit. Then there were the Refugees, who were Loyalists that organized into militia raiders and operated somewhat under the authority of the British Army. Benjamin Franklin’s son, the former Royal Governor of New Jersey William Franklin, was the leader of a Refugee band until his capture. With all of these forces at work the terrorized population might be raided and robbed by either side or even both no matter what position they took politically.

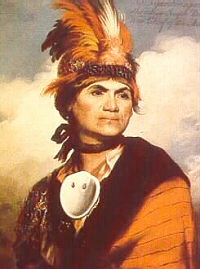

South of New York lay the Ramopo Mountains, where the infamous Cow-Boy of the Ramopo’s Claudius Smith pillaged. A French & Indian War muster roll claimed that Smith was 5ft 9in but he was so feared that when a warrant for his arrest was issued, he was reputed to be 7 ft tall. Smith’s gang, including three of his sons, took part in quasi military raids with the infamous Mowhak Chief Joseph Brant,