Fright Night

by

D.H.T.Shippey & Michael Burns

Children going door to door. Costumes on parade in the streets. Bonfires with shadowy figures dancing around them. No, it’s not Halloween; it’s Pope’s Night in 18th century Boston.

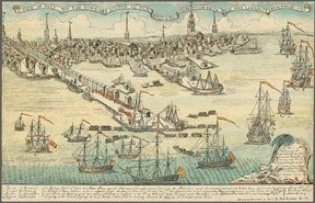

While the origins of our modern Halloween have their roots in the traditions of many medieval countries, 1700’s Boston had its own night of fright and frolic. It may be hard to imagine an anti-Catholic Boston today when we so associate Bean-town with the Irish, the pubs and the Kennedys, but in the 18th century it was just that. Each year on November 5th the town became a wild party celebrating the very anti-Catholic Pope’s Night. As you will soon see, many of the Halloween traditions we have today seem to clearly parallel this ancient celebration of religious intolerance.

Massachusetts in the 1700‘s was a very English colony, and England’s enemies were France and Spain (both Catholic). England had suffered and survived through civil wars between Catholic and Protestant royals and the attempted destruction of Parliament by the infamous Catholic partisan Guy Fawkes. Back in Mother England, the celebration of Guy Fawkes Day was a long established annual observance, with fireworks and the burning of large Guy Fawkes effigies. Massachusetts carried on that tradition, but seems to have taken its contempt for the Catholic Church further by turning Guy Fawkes Day into Pope’s Night and Boston into the center of the celebration.

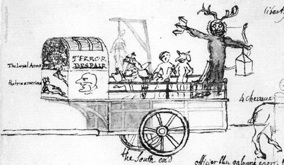

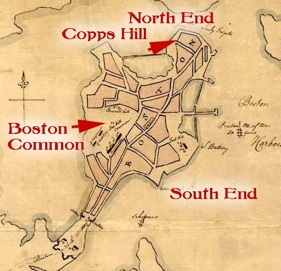

The revelers were divided into two rival factions: North End and South End. In the days leading up to Pope’s Night the young boys would go door to door ringing bells and carrying hand made Pope figures that were dressed wildly and seated on boards or small carts. These were meant to act as concept models for giant figures built by the opposing sides and placed on decorated carts similar to modern Mardi Gras parade floats. As it was printed in a contemporary broadside verse

“The little Popes, they go out First,

With little teney Boys:

Frolicks they are full of Gale

And laughing make a Noise.”

As the boys came to the door of a house they would call out

“Don’t you hear my little bell

Go chink, chink, chink?

Please to give me a little money

To buy my Pope some drink.”