Ghost In The Machine

by D.H.T. Shippey & Michael Burns

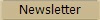

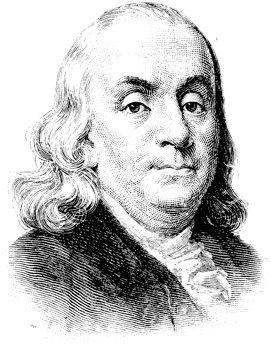

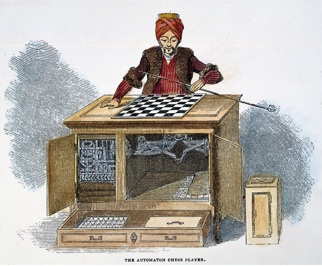

In 1783, Benjamin Franklin received a fascinating invitation. A mechanical genius by the name of Wolfgang von Kempelen had built a machine known as The Turk that challenged Dr. Franklin to a game of chess.

Dr. Franklin was known to be an avid chess player and had even written on the subject. When he came to his match against The Turk, he knew the machine’s reputation. It had beaten some of the best players in Europe and had an impressive but not perfect record of winning. It was an aggressive player that usually defeated opponents within half an hour. As the game was played, Kempelen would occasionally make small adjustments to the mechanical parts on the figure, but nothing that could possibly affect the game. When it was all over, Franklin wrote that it was one of the most enjoyable games of chess he had ever played--a pleasant way of saying he lost. This would make Benjamin Franklin the first American to experience being defeated by a machine, something most Americans today could certainly relate to. Franklin, always the diplomat, was a gracious loser in spite of the fact that he suspected somehow the machine was an illusion and that someone was manipulating it. Even with all his belief in science and innovation, he just could not fathom how a machine might think.