The Great Gaspee Affair

by

D.H.T.Shippey & Michael Burns

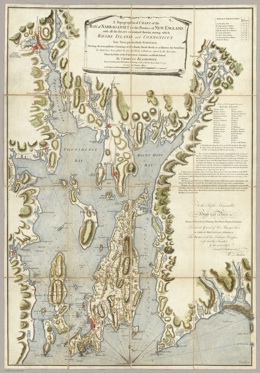

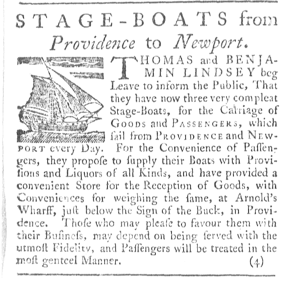

The lean 28-year-old stood on the deck with the confidence of command and the invincibility of youth. Captain Benjamin Lindsey saw the smoke belch from the cannon’s mouth before the shot could be heard. The ball crossed to his port side ahead of his bow, as he knew it would. It was meant as a warning to drop anchor and be boarded or suffer the consequences. Now the chase had begun, and Lindsey barked orders to the sailors on the little packet ship Hannah. His Majesty’s revenue schooner Gaspee was ready and eager to pursue. Lindsey knew the ship he was facing was the most detested vessel in the waters between Rhode Island and Boston, and commanding her was possibly the most detestable of men, Lieutenant William Dudingston.

Dudingston had earned the enmity of most of Rhode Island in his four months on Narragansett Bay. He stopped and searched ships without reason or warrant. He insulted, harassed, humiliated, and even beat Americans who he felt had offended him. He confiscated any supplies or materials he wanted from both ships and local farmers. Worse yet, to the residents of this maritime based economy, Dudingston made a practice of seizing the ships of smugglers and honest merchants alike, and sending the seized ships to Boston. Sending them to Boston instead of local Rhode Island courts made it extremely expensive and difficult for the merchants to reclaim their seized goods and ships. By the time the property had been reclaimed, a merchant might be financially ruined. For the people of Rhode Island, Dudingston was the perfect example of government oppression in America.

Lindsey kept his heading toward Providence, a move that was sure to make Dudingston smile. Since the bay quickly narrowed on approach to the town, Dudingston undoubtedly believed he had his quarry neatly trapped. Lindsey’s time was short, but he had a chance to make good his escape. He had years of experience sailing the waters of Narragansett; he knew every corner of the bay under every condition. The Gaspee was closing in as they headed north past Namquid Point. As the Hannah began to change heading to port, Gaspee was quick to counter, making sure the Hanna could not escape back to the South. With the shoreline coming up, Lindsey gave the orders to pull to starboard, with the Gaspee now breathing down their neck. Dudingston’s prey was almost in his grasp when the most horrific groan came from beneath the deck. Dudingston and most of the Gaspee’s crew was thrown forward. The small and currently empty Hanna had sailed lightly over Namquid Point - submerged only a few feet under the high tide.

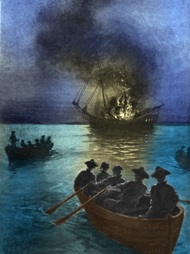

The Hannah arrived in Providence in the early evening. Lindsey made a beeline to Merchant John Brown, notifying him that the Gaspee was stranded. Brown (a wealthy and politically powerful merchant) wasted no time getting word out about the predicament in which Dudingston and the Gaspee had found themselves. Drums were beat and cries announced the news through the streets. They had less than nine hours before the Hannah and her crew would be freed by the tide. Brown called his trusted captain Abraham Whipple and any other interested men to a meeting at Sabin’s Tavern, where they planned an expedition to attack the ship. Eight whaleboats filled with 65 volunteers rowed out that night near 10 o’clock. Many more citizens lined the docks and watched them go. It was the night of a new moon, with darkness wrapping the little boats as they employed muffled oars to hide their approach. By the time the Gaspee’s watch on deck detected the civilians’ boats, they were too close to aim the deck guns at.