I’ll Be Home For Christmas

by D.H.T Shippey & Michael Burns

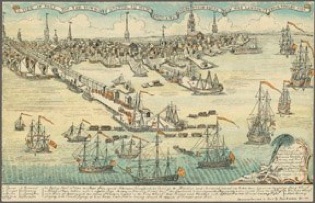

The soldiers marched eight abreast in their worn coats and shoes while the cheers of New York’s patriot citizens poured over them. Riding at the front of this honor guard of 800 men was their General. Washington had taken that title near the start of war eight years earlier with a bit of grey frosting his red/brown hair. Now, peace would find him a man with almost completely silver hair and a face lined by the years of service. Citizens, who until recently had been out of necessity hiding their support of the American cause, wore sprigs of green in their hats and joined the parade through the streets. The last British soldiers had just departed from the city; victory was now complete. It was November 25th, 1783.

Washington had been prepared for the official withdrawal of the British troops for months as details of the peace treaty were completed. In all the years of the war he had only returned home once, briefly, on his way to Yorktown. Even that had been a visit filled with military planning and preparation. Now he was making the plans he had long dreamed of--a return to his home, his farm, and his wife. He only had a few duties that remained before he could begin again his life as George Washington the farmer.

The time from November 25 to December 3rd were filled with dinners, ceremonies, parties and fireworks. At every turn there was another official that wanted to host an event that honored the victorious Washington. Politicians are politicians in any era, and to be associated with the most powerful man in America was a winning strategy for those who themselves sought power in the young republic. Washington was well aware of what was going on. He had once himself been a young candidate to the House of Burgesses in Virginia seeking votes. The defining difference between Washington and most politicians of the day was his desire to perform his duty honorably rather than seek further power. As a young man he may have sought power, but watching the country thrown into war over abuse of power had made him wary of its temptations.

December 4th was the day that Washington had set for his departure to head South. The receptions and dinners now completed, he had one last event that lay before him; his farewell to his officers. Some of these men had faithfully served through the entire war. General Henry Knox had been only a 25 year old captain in the Boston militia when he first served under Washington. Others had been mere boys when they began. In eight years of fighting, some of these officers had become as close as family. One who should have been among these heroes (Arnold) had betrayed Washington. Many who were absent from this final gathering had fallen along the way, including Washington’s dear friend Hugh Mercer and his own stepson Jackie (John Parke Custis.) Assembled there in the long room of Fraunces Tavern were the surviving heroes who had endured the days when there seemed to be no hope for Liberty and Independence and had seen the defeat and departure of the most powerful army in the world. Washington raised a glass of wine and found himself barely able to speak, overcome by emotion.

“With a heart full of love and gratitude,” He paused to compose himself. “I now take leave of you. I most devoutly wish that your later days may be as prosperous and happy as your former ones have been glorious and honorable.”

They all drank, not with boisterous cheers but muffled overwrought approbation.

Washington continued, “I cannot come to each of you, but shall feel obliged if each of you will come and take me by the hand.”

The first to come forward was Knox, whom Washington embraced and kissed through tears. Then began the line of men. Each man stepped forward, clasped the General’s hand and wept openly, speaking no words. What could be said? What words could express what they had seen together, done together, these men who changed the world? They were parting from a man who had never left them for a furlough the whole of the war but led them throughout. After every man had received Washington’s hand the General walked silently across the room and raised his arm in wordless farewell. He stepped out and did not turn around again but walked in silence to the docks. He had entered New York to cheers and a parade; he now departed with a parade of noiseless officers walking in procession behind him.

The ferry took Washington across the Hudson with Christmas gifts that he planned to give to Martha and their grandchildren back home at Mount Vernon. In the 18th century gifts might be given at any time during the twelve days of Christmas between December 25th and January 6th. Washington was planning on spending his first Christmas at home in eight years and had only one final task to perform as Commander and Chief of the Army. It was perhaps the most important duty he would perform in the whole war. Washington was preparing to resign. In a final statement of Liberty and the establishment of the American Republic, the most powerful man in the country was returning that power to the people who had trusted him with it. History is full of victorious Generals who seize the reigns of national power, but holds very few stories of those who willingly and deliberately relinquish their power.