Restoration

by

D.H.T.Shippey & Michael Burns

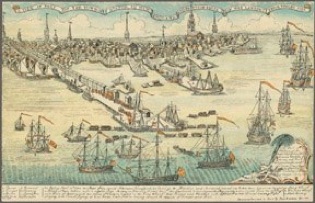

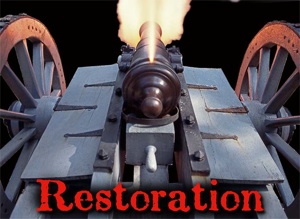

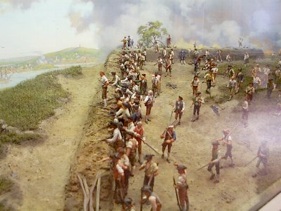

American General Israel Putnam had given the orders on where to place the cannons. His men were to cross the small strip of land towards Charlestown and take up semi-entrenched positions on Breed’s Hill. One artillery company, in fear, had already disobeyed and stayed on the mainland. Captains Samuel Gridley and John Callender were terrified as they brought their guns to the redoubt. John Callender had been elected by his neighbors and fellow militia members to be the commander of his artillery company. The respect and confidence shown by his neighbors had brought him, with thousands of others, to surround Boston after the battles of Lexington and Concord, and now to the field of what would be known as the Battle of Bunker Hill. The British ships began to rain fire down on Charlestown, and boats full of professional soldiers in red coats began landing on the shore.

Callender and Gridley saw what was happening around them, and were terrified. It’s easy to understand how panic and fear could consume men in battle. In the 18th century battle plans were designed to make the enemy give up the field in fear. The power of the British Army was in their discipline; they followed orders and moved forward like a machine. Callender and Gridley had already been defeated; fear had already overcome them. They were sure that their position would be overrun and decided to retreat across Bunker Hill, just behind Breed’s Hill. The artillerymen could be seen dragging the guns from their redoubt and harnessing the horses to drive the guns away. They were about to begin their dash back across Charlestown Neck, leaving their fellow soldiers alone to defend the hill without artillery support, when General Putnam stopped them. The Captains claimed that they were out of ammunition, but Putnam threw open their side boxes to find them full of 3 lb. cannonballs.

We all know the story of the Battle of Bunker Hill (Breed’s Hill) and the brave militiamen who fought and held back waves of British Soldiers. Eventually, of course, the numbers proved too great and the ammunition did run out. Bunker Hill was an American defeat, but the cost to the British was incredibly high. Almost a third of their troops were casualties. The Americans, with few casualties, were able to regroup. Their willingness to stand and face the might of the British Army converted many to the side of the Patriots.

Less than two weeks after the battle, George Washington took command of the American Army and General Putnam demanded that Artillery Captain John Callender be cashiered or shot for his cowardice. A committee of Congress submitted a report on the misconduct of officers at the battle, and a Court Martial was begun. John Callender was found guilty of cowardice in battle and sentenced to be cashiered. General Washington approved the sentence, stating as he did so, “It is with inexpressible Concern that the General upon his first Arrival in the army, should find an Officer sentenced by a General Court-Martial to be cashier'd for Cowardice. A Crime of all others, the most infamous in a Soldier, the most injurious to an Army, and the last to be forgiven-The General having made all due inquiries, and maturely consider'd this matter is to led to the above determination not only from the particular Guilt of Capt. Callender, but the fatal Consequences of such Conduct to the army and to the cause of America.”