by Dan Shippey &

Michael Burns

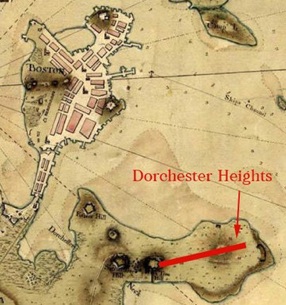

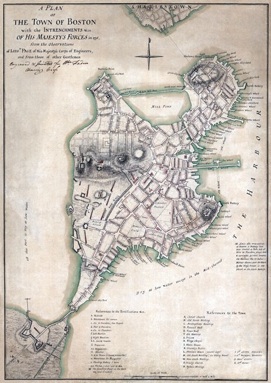

When George Washington arrived at Cambridge, Massachusetts in July 1775 to take command of the new Continental Army, he was joining a fight already in progress. The British army now bottled up in Boston had been occupying that city for eight years. The Massachusetts farmers, merchants and artisans who made up the Patriot forces had chased the British Ministerial Troops from Concord back to Boston two and a half months earlier and had fought the Battle of Breed’s Hill (Bunker Hill) almost three weeks prior. The only way on or off the small patch of land that was Boston was by boat or the narrow strip of earth called Boston Neck, where the Patriots had drawn up their lines. Both sides had settled in, and neither side knew exactly what to do to break the deadlock. Even though they were trapped, the British had some advantages in the town. They had control of the port and could resupply from the sea. They were professional soldiers and the strong arm of one of the 18th century’s superpowers. The Patriots had no established source of provisions and arms, and no real order or leadership structure. Washington came to change that.

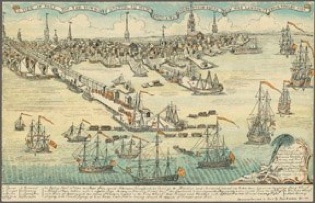

The crisis in Boston did not spring up overnight. In 1768, the British Government decided that they would send soldiers to enforce the customs laws (indirect taxes) that the American Colonists had been opposing for the past two years. It was against British law to send an army of occupation to a British city, and Bostonians, already angry about taxes that were illegal according to their Royal charter, were irate over this direct breach of the British Constitution. Eventually there were more than 4000 soldiers living in a city of under 20,000, roughly 1 soldier for every 5 citizens. British warships sat like brooding sentinels in the harbor with their guns facing the town. To say that the living conditions were tense is a gross understatement. Clashes between citizens and soldiers were chronicled in local pamphlets and newspapers, which exaggerated these stories to further inflame passions. No one should have been surprised in 1770 when the Bloody Massacre, better known today as the Boston Massacre, occurred. Looking back, it seems obvious where things were heading; in 18th century Boston things were not so clear. The chain of events continued with the Tea Party in December of 1773, the Powder Alarm in September of 1774, and culminated in the shots fired at Lexington and Concord. Within days of the British retreat into the city, 20,000 minutemen, militia and would-be soldiers flowed into the area surrounding Boston.

The siege dragged on for months, devolving into sniper attacks, raiding parties and minor skirmishes. Washington did his best to instill military discipline in his very independent minded young Army, and pleaded with Congress to send supplies. That Fall a 25-year-old bookseller-cum-soldier approached Washington with a plan to break the Boston deadlock. As a young officer, Washington had been frustrated when his commanding officer refused advice from anyone junior to him, so he made a point of listening to his men. The young merchant standing before Washington hardly looked the part of a great leader. He was overweight, over tall, and had lost a thumb to a gun accident. Still, he was brave, determined and had educated himself by reading every military book in his shop. Henry Knox suggested an ambitious plan to take the 59 cannons and mortars from Fort Ticonderoga (recently captured by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold) and bring them 300 miles to Cambridge. Others thought the young man was being ridiculous, but Washington gave Knox a Colonel’s commission and ordered him to retrieve the cannon. The adventure that followed is worthy of it’s own film. Over the course of three months (Winter months) Knox moved 60 tons of cannons and other armaments by boat, horse, ox-drawn sledges, and manpower, along muddy roads, across two semi-frozen rivers, and through forests and swamps. On January 27th 1776, he arrived with the artillery.