The Great Raid of 1779

by Amber Hammrich

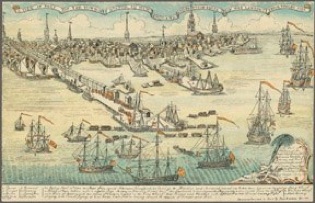

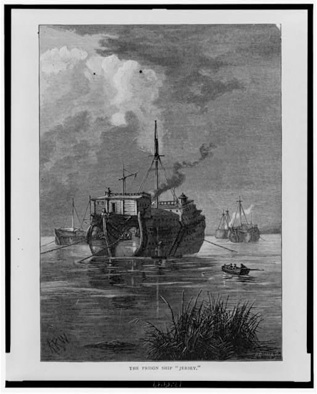

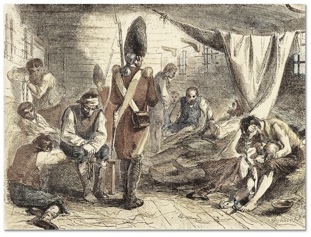

She drew her cloak about her face to protect against the biting winds and tucked her basket of food closer to her to prevent the food inside from turning cold. “This way,” a British guard in a woolen red uniform growled, gesturing with his musket the direction she should go. The guard was a hard man, and his appearance matched his temper. His teeth were blackened and crooked, he had an ugly scar on his cheek, his wide mouth was etched into a permanent scowl, and his stride was haughty. They stopped in front of a wooden trap door. She could already smell the familiar smells of death and sickness before the guard even opened the door. “Creeak.” The eerie sound jangled her tense nerves as the guard opened the trap door. Hundreds of shivering, ill-clad, emaciated, and filthy American prisoners crowded the stairs leading down below decks. “Back!” The guard cried, swinging his musket wildly, the bayonet’s steel glinting off of the dim whale oil lantern that a British guard behind them carried.

Her name was Elizabeth Burgin. We would not know her name or even of her aid towards the American prisoners if we did not have the following letter written by George Washington to the Continental Congress:

“Regarding Elizabeth Burgin, recently an inhabitant of New York. From the testimony of our own (escaped) officers…it would appear that she has been indefatigable for the relief of the prisoners, and for the facilitation of their escape. For this conduct she incurred the suspicion of the British, and was forced to make her escape under disturbing circumstances.”

But, who was Elizabeth Burgin? How did she free prisoners without the guards knowing? How did they finally discover her part in the missing prisoners? These questions are difficult to answer. As to the first question, not much is known about her early life or her marital status at the time she freed the prisoners, but we do know that she lived in New York during the American Revolutionary War and was the parent of small children. She was obviously a staunch patriot who had heard about the terrible suffering American prisoners were undergoing on the hellish prison ships in Wallabout Bay. Since only women were allowed into the prison ships, she visited the prisoners as often as she could. She brought food, comfort, and cheer to the discouraged Americans.

An American officer named George Higday was part of Washington’s secret Culper Ring in New York. His name is mentioned for the first time in General Washington’s correspondence on June 27, 1779. George Washington was casting about for an agent to spy on the British in New York. George Higday was brought to the attention of Benjamin Tallmadge and General Washington by three officers whom he freed from captivity on Long Island. These were the same officers Elizabeth Burgin mentions in her letter to General Washington on November 19, 1779. “…Major Van Burah, Captain Crain, Lieutenant Lee, who made their escape from the guard on Long Island.” Washington suggested to Benjamin Tallmadge, who was then in Connecticut, that he contact, “a man on York Island, living on or near the North River, of the name of George Higday.”

It seems that George Higday was secretly freeing American prisoners (mainly officers) and might have already been helping the Culper Ring spy on the British in Long Island. In General Washington’s words, George Higday: “hath given signal proofs of his attachment to us…” (Emphasis mine). If this is true, how does Elizabeth Burgin fit into this picture? How did George Higday know about her? Was she part of the Culper Ring? Was this plan to free the American prisoners birthed in General Washington’s headquarters? A tantalizing hint that this might have been a planned event is found in Elizabeth Burgin’s letter, “George Higby brought a paper to me from your aide directed to Colonel Magaw on Long Island.” Colonel Magaw was an American officer who had been in captivity on Long Island ever since the fall of Fort Washington in 1776. General Washington could still have been in contact with him via one of his aides, as Elizabeth Burgin states. Also, if George Higday was a spy, then he could easily have slipped into Colonel Magaw’s quarters to pick up the letter. George Higday then would probably have approached Elizabeth Burgin with this plan to free the prisoners, asking her to participate, knowing that only women were allowed on the prison ship. He wanted her to tell the prisoners of his plans and to prepare for their escape. He told her to free two hundred prisoners, which she did. How she smuggled them out is up for conjecture; we are given no clues to aid us in figuring out how or when.

Elizabeth Burgin does not say what was written on the paper, but then again, if it was top secret, she had a purpose for not disclosing it in her letter to General Washington. If this was a planned event, that could explain the “friends” who helped sneak Elizabeth away from captivity in New York, and it could explain how she was able to free two hundred prisoners. It could also explain why she is vague in her letter about how she freed the prisoners. She might have been trying to protect the identities of the people who helped her. If this was orchestrated by General Washington, then this was the first major Great Raid in U.S History!

Unfortunately, General Washington’s letter to Benjamin Tallmadge was intercepted by the British a week after he wrote it. Colonel Banastre attacked Benjamin Tallmadge’s camp at about five in the morning on July 2nd, 1779. The British dragoons were beaten off, but not before they stole twelve horses, including Benjamin Tallmadge’s horse with the letter about George Higday in the saddlebags.