The One Third Myth

by Dan Shippey &

Michael Burns

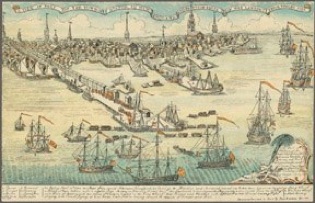

Anyone who has spent time studying, learning or just hearing about American Revolutionary War history has probably heard the following statement:

The Patriots made up only one third of the American population during the War for Independence. One third were Loyalists that supported the King, and one third remained neutral.

I heard it said in a TV documentary just the other day. You might have heard it from a teacher, a friend, a tour guide, or even an historian. Some people say it in support of their cause, i.e. “We don’t need a majority; we just need a determined minority like the Founders had.” Some people state it as a fact to demonstrate just how much the Patriots were underdogs in the struggle for Liberty. No matter who says it, however, or why, it just isn’t true.

Myths can be useful when they illustrate a virtue or help us remember a cultural value, but a widely accepted historical myth is dangerous. It is dangerous because it can create a foundation for misunderstanding our history and distort the nature of the people and events we study. In the end that can mean we get a distorted view of ourselves and our place within the story of history. The “one-third” myth would lead us to believe that our founders forced their minority beliefs on a majority of the population, causing eight years of violent conflict--an idea that would have horrified the Founders.

Back in 1975, historical scholar William F. Marina tried to sound the alarm that the one-third myth was becoming widely accepted as a historical fact. Marina dug in to trace the origins of the myth and showed where errors had been made and how they had been repeated again and again. His work led him back to the first printing of the myth in George Sydney Fisher’s, The True History of the American Revolution from 1902. Fisher wrote the following, even quoting a letter from John Adams (Yes, that John Adams).

“Adams compiled to the best of his ability, and did not think it necessary to count the neutrals and hesitating class, or to exaggerate at all the numbers of the extreme loyalist. Many years after the Revolution, in 1813, he said that the loyalist had been about a third, and he was then evidently counting the first and second classes. In 1815 he said substantially the same, and gives an interesting estimate which is very like that of General Robertson.

If I were called to calculate the divisions among the people of America, as Mr. Burke did those of the people of England, I should say that full one third were averse to the revolution. These, retaining that overweening fondness, in which they had been educated, for the English, could not cordially like the French; indeed, they most heartily detested them. An opposite third conceived a hatred of the English, and gave themselves up to an enthusiastic gratitude to France. The middle third, composed principally of the yeomanry, the soundest part of the nation, and always averse to war, were rather lukewarm both to England and France; and sometimes stragglers from them, and sometimes the whole body, united with the first or the last third, according to circumstances.”