The Pri¢e of Thing$

by Dan Shippey & Michael Burns

John Adams did not use Pay Pal, Ben Franklin never kept an American Express card, and George Washington never paid with a dollar that had his portrait on it. All of these men, however, operated businesses that dealt with banks, loans and credit. When studying the colonial and revolutionary era, Americans are quickly faced with records of purchases in pence, shillings and pounds as well as dollars. The routine question asked by the student at some point is, “How much is that in today’s’ money?” The last thing our intrepid student wants to hear is, “It’s complicated,” but that is what they usually get. The truth is that you can’t make exact translations because we do not put the same value on things that people did in the 18th century. We highly value the labor that goes into hand made work. In the 18th century, everything was hand made and labor was not your major expense. There is no 18th century minimum wage or hourly rate, and things we take for granted--like chocolate--could easily cost more than a day’s labor.

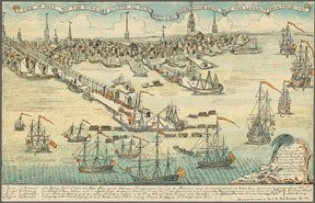

Let’s take it step by step. Although cold hard cash (coins) have always been the currency of choice, England liked keeping silver out of the colonies. This made the colonies strictly dependent on trade with England and English credit. So business on a daily basis might just as likely be conducted by barter or credit but would still be measured and recorded in Shillings and Pence. Unlike our simple 100 pennies = $1.00 formula the value of 1700s English currency worked like this:

12 pence (12d) make a shilling

20 shillings (20s) make a pound (£ 1)

So 1 pound, 2 shillings and 4 pence would be written

£ 1.2.4

Ah, but even the lowly penny 1d could be divided into quarters called a farthing (fourthing) and 2 farthings were a ha-penny (half penny pronounced hay penny)

I know, you are ready to declare independence already, right? But these measurements were as natural to the colonials as our system is to us today. Stick with it just a little longer and things will get easier.

Although coins were always in short supply, the coins used (deep breath) were farthings, ha-pennies, pence (plural of penny), shillings, crowns, sovereigns and guineas.

A Farthing is a “fourth-ing” 1/4 of a Penny

2 Farthings = 1 Halfpenny (ha-penny)

4 Farthings = 1 Penny (d) (Pence is the plural of Penny)

5 Shillings (s) = 1 Crown

4 Crowns = 1 Pound sterling (£) (gold sovereign)

21 Shillings (s) (or 4 Crowns + 1 Shilling) = 1 guinea

So, now that it is all clear as mud to you, you should know that the colonials traded in foreign coins as well. It was fairly easy since the value of the coin was measured by the weight of silver or gold within. The highly coveted Spanish milled dollar became the denomination that our currency was modeled after during the war and ever since, but that is another article. I will close this section by saying the exchange rate in the 1750’s was 7 Shillings 6 pence to make a Spanish dollar (1 dollar = 0.7.6d)

Nothing that has come so far in this article has really been able to tell you the value of that money as far as purchasing power. Now that we are clear on our definitions (you are clear now, right?) we can continue on.

Wages were different in different colonies (really like independent countries) but in Virginia a farmer might make £ 10 per year while a skilled craftsman might make an annual income between £ 30 and £ 100. A wealthy plantation owner might see an annual income of £ 1,000. If a lesser craftsman was making £ 30 a year it would break down to about 2d (2 pence) an hour. That might be closer to 1 and 1/2 pence an hour when you figure a six day work week of about 10 hour days.

Ok, so now we are getting closer to understanding the value of your labor and why it was way better to be a plantation owner than a simple farmer (no surprise there). Now the next step is looking at what your purchasing power would be.