UNDER SIEGE

by Dan Shippey & Michael Burns

Looking out from Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Congress could see soldiers moving in with muskets to surround the building. They wanted to call on Continental Army troops to protect them, but there was a problem; the Continental troops were the ones surrounding them.

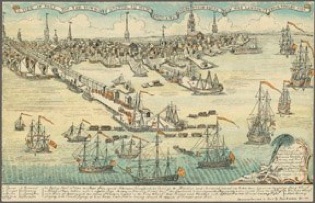

In June, 1783, the Revolutionary war was over. While some small details of the Treaty of Paris were still being worked out, all of America knew that peace was at hand. More importantly, the Army that had fought and won independence knew peace was at hand. The army was going to be largely disbanded and sent home to their farms, businesses and families--but without the pay they had been promised. In fact, the Congress had been delinquent in paying their soldiers for some time and was not showing any signs of planning to pay them. The soldiers had just fought a war for rights they had been promised and denied by the Government of England; they were not about to let their newly formed Government deny them what had been promised. The men knew that if they disbanded and went home they would be powerless to demand their pay, so on June 17, 1783 Congress received a message from Soldiers of the Continental Army stationed at Philadelphia. The message insisted upon payment for their service and threatened action if their grievances were not redressed. Congress ignored the message.

Two days after their first message, approximately 80 soldiers left their posts and joined forces with soldiers stationed in the Philadelphia City barracks. As the number of soldiers swelled to around 500, the men seized control of the weapons stores. Surprisingly, Congress still did not seem ready to answer the soldiers’ complaints; so on the morning of the 20th around 400 armed soldiers marched on Congress and surrounded Independence Hall. Now under siege, the Congress wanted to leave the building; however, the door was blocked by soldiers demanding their pay.