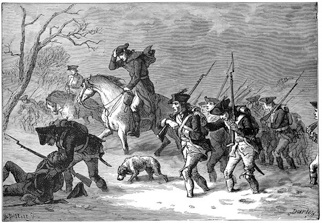

Food was at a severe low. Half rations were the norm when the army moved into the camp, and now with supply lines failing or freezing up altogether those rations sometimes became non existent. Foraging could only be carried out to small extents. Hunting was not practical with a soldier’s musket, and pillaging the already surly citizens was both illegal and dangerous, yet both these occurred from time to time. A full ration of food would have been similar to this General Order from January 1780:

A pound. of hard or soft bread & 19 Pound of Indian (corn) Meal or a pound of flower, a pound of Beef or 14 oz. Pork to be daily Ration until further orders.

But documents and records show that a quarter of that would have been far more likely when there was any food at all.

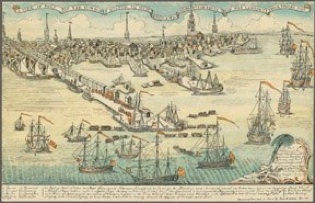

If things were not dreary enough for Washington and his troops, add to this the court martial trial of a Patriot hero. Washington’s friend and favored, General Benedict Arnold, was summoned to arrive the 19th of December even though his Court Martial had officially begun in June. Arnold was to be tried for permitting a Tory vessel to enter the port of Philadelphia without acquainting other officials of the fact, as well as 12 other counts of misbehavior, including misusing government wagons and illegally buying and selling goods. The court martial convened at the old Dickerson Tavern in Morristown. In his defense, Arnold presented letters from Washington which praised his bravery and victories in the cause of Liberty. The trial continued without pause through Christmas Day and on into January. In the end, Arnold was exonerated of most of the charges and only had a letter of reprimand added to his record. Arnold’s reputation, which was all important to the vain and insecure Arnold, had been sullied by the affair and the seed of his anger already taken root. Since June, Arnold had been transmitting military intelligence to the British. Now, in the coldest winter, anger had blossomed into full treason.

The army would emerge from the winter of 1779-1780 smaller and perhaps weaker than at any other point in the war. Washington would remember it as the worst of times. Three more years of battles, victories, defeats and betrayals lay ahead. What the Army did in that, the longest hardest winter, was survive, and because it survived the idea of America did as well.

You can still visit the camp at Jockey’s hollow where the patriots starved and froze. Some cabins have been reconstructed as they were at the time, and the Ford house that served as Washington’s headquarters still stands as a museum today. Interestingly though you rarely hear of people going to visit it in the winter.

For past articles go to

http://www.breedshill.org/The_Breeds_Hill_institute/Past_articles.html