Giant part 2

by D.H.T. Shippey & Michael Burns

When we last left Peter Francisco, his fame as a heroic figure had been secured. He provided cover for sharp shooters at the battle of Brandywine creek and was wounded in the process. He fought at Germantown and Fort Mifflin. He survived camp illness at Valley Forge. He fought at Monmouth Courthouse and was wounded again, and again slashing his way with the first raiders into the fort at Stoney Point. Francisco’s 2nd term of service had expired, and he was going home to Virginia. All that had been asked of Francisco he had done--and then some. Now was Francisco’s time to enjoy the Liberty he had been fighting for.

The war, however, was not finished with him.

In 1778 the British had developed a new strategy. The strategy in the North had bogged down since the Battle of Saratoga in late 1777. Boston had been lost early in the war and holding Philadelphia was costing money without bringing the British any closer to victory. New York was successfully pacified but the countryside around it was a danger zone with rebellious civilians, militias and robbers raging their own battles. So the new goal was to split the South from the North and use the Loyalists they believed would rally to the British flag to secure the Southern Colonies. What resulted was almost a civil war, with Loyalist American militias fighting Patriot American militias in battles and skirmishes that often pitted neighbor against neighbor. When Peter Francisco understood what the British were doing, he left his home again and joined the Virginia militia.

The first major battle in the Southern campaign was the battle of Camden on August 16, 1780. Meeting the British forces at Camden, the overconfident and under-skilled General Horatio Gates severely misjudged the abilities of his largely untrained militia troops. In spite of superior numbers, Gates’ troops suffered a horrendous defeat that sent them scrambling in panic from the field. In the middle of the smoke and carnage, Peter Francisco appeared again. With the Continentals partially surrounded and trying to flee, a British soldier took aim at Francisco’s exhausted commanding officer, Colonel Mayo. Francisco shot the soldier first. It seems that the rest of his Comrades continued their frenzied retreat while Francisco turned to fight. A dragoon charged toward the Virginia giant, but before he could strike Francisco impaled the rider with a bayonet and lifted him clean off his horse. He grabbed the reigns and leapt into the saddle, riding through the enemy lines. He pretended to be a Tory, yelling as if encouraging them to catch the rebels. Once he had caught up with his fellow soldiers and found Colonel Mayo, he dismounted and lifted the officer up into the saddle. Mayo ever after gave credit to Francisco for saving his life. Soon after it is said that Francisco saw a retreating cannon stuck with a broken carriage. Unwilling to let the cannon fall into enemy hands he lifted the nearly 1,100 lb. cannon himself and placed it in a wagon to be safely evacuated. While hard to believe such a feat, by this time Francisco had become a legend referred to as the “strongest man in the army.”

After Camden the army was in complete disarray, and it seems Gates himself rode off, abandoning his soldiers to their fate. He would never lead an army in battle again. Meanwhile, Peter Francisco had now found a horse and joined Captain Thomas Watkins’ new cavalry troops under Colonel William Washington.

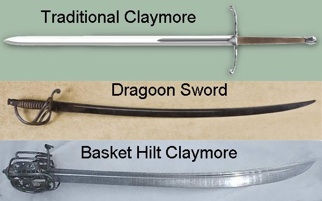

Somewhere in this time it is believed that Francisco got his legendary sword. Generally, swords were carried only by officers and dragoons (cavalry), though exceptions can be found. It would make sense for Francisco, now serving as one of William Washington’s mounted troops, to carry a sword. Some say that it was given to him by his friend Lafayette, while others say it came from General Washington at Lafayette’s request. Still others have theorized that Francisco himself might have made it at his forge. Whatever the case, the storied sword was described as both a saber and a claymore, with a blade five feet long and a foot-long handle. This makes us think of a William Wallace style two-handed sword (ala Braveheart). Given the time period, it is more likely to refer to a basket hilt blade, probably even curved like a regular horseman’s saber. Whether it was truly six feet of sword is hard to say, but those who saw it believed it so.

The Continental army was now under the command of General Nathaniel Green, who seemed to understand his troops and the nature of the war in the South far better than his predecessor. He had forced British General Cornwallis to chase him around the South, exhausting the British troops and their supplies. Now Cornwallis had to demand supplies at the point of a bayonet from the citizens and farmers he had previously hoped would support the British efforts. After the British defeat at Cowpens, Cornwallis was looking for any opportunity to destroy Green and his army. When he heard that Green was camped near Guilford Courthouse, he believed he saw his chance.